By David Harrison

In my book The Genesis of Freemasonry I put forward how Dr Jean Theophilus Desaguliers was responsible for creating the third degree sometime in the 1720s. Before this, there were two ‘parts’ being performed; the Entered Apprentice and the Fellow Craft. The new three degree style ritual soon spread. It seemed that Freemasons soon wanted to explore deeper pathways within Masonry, leading to new ideas being developed. Chevalier Ramsey was a Jacobite Mason who had gone to France to tutor the sons of aristocrats, and in his Masonic address in 1737, he famously outlined that Freemasonry was linked to the Crusaders and Chivalric Orders. His Oration put forward that after being preserved in the British Isles, it was transported to France, and though there is no evidence that Masonry was associated in any way to the Crusaders or Chivalry, it does show that at the time there was a developing interest in Chivalric Orders in relation to Freemasonry. Though Ramsey did not set out any plans for new Chivalric Masonic Orders in his ‘Oration’, his address certainly assisted to inspire them.

The Craft rituals at this time were far from standardized and this created liberty to explore new stories, to create sequels to the Hiramic legend and the building of the Temple. All this was happening during a time when English Freemasonry became split and was arguing over how the Royal Arch should fit into the system. On the Continent however there is indeed a rich and fascinating tapestry in regards to the development of Masonic Rites, some of which can be linked together during this heady manic period for access to High Degrees in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As Masonic historian Lionel Seemungal once wrote ‘the surviving degrees and orders are the distilled essence of the past’, the lifeblood of some of the degrees that we practice today having their origins in these lost degrees. With the egos of the men behind them and a dangerous blend of politics, magic and power, Freemasonry was taken into a very experimental place, a place where we will now explore.

The Rite of Strict Observance

Josef Friedrich August Darbes, A portrait of General of the Artillery Pyotr Melissino (responsible for the Melissino Rite), circa 1773-80, Kursk Gallery

There was a strong desire to extend the themes explored in the Craft rituals, and there were plenty of charismatic characters that were eager to create or promote new Orders and Grades based on the continuation of the themes for the search for lost knowledge. One such charismatic individual was Baron Karl Gotthelf von Hund, who in around 1754, founded the Rite of Strict Observance in Germany. Baron von Hund had put forward that he had been initiated into a mysterious Masonic Order of the Temple in Paris in 1742 and that his secret knowledge had been gained from ‘unknown superiors’. The Rite of Strict Observance became a rather popular Rite, spreading to many other European countries such as Switzerland, Holland, Denmark and Russia, and included a tantalising seven degrees, offering the philosophy of progression to willing Masons.

These seven degrees, according to the transcription of the Schröder rituals by Alain Bernheim and Arturo de Hoyas, included the first Craft degrees of Apprentice, Fellow and Master Mason, followed by Scots Master, Secular Novice, Knight, and finally Lay Brother. The three Craft rituals are recognisable to any Mason, but nonetheless have stark differences, such as in the Master Mason degree which features a ‘Cassia branch’ instead of the Acacia sprig we know of today. A collection of Catechisms are presented that seem quite unusual in certain contexts, and it appears that the rituals evolved down a very different path, though still retained the essence of the first three degrees. The Rite was Templar orientated, its chivalric content and the mystery that surrounded its origin still tantalising Masonic historians today; the translations of Berheim and de Hoyas in discussing the ‘Extracts From the History of the Order’ present a story of how a number of Templars fled persecution in France in 1311 and arrived in Scotland, clothed as Masons. According to the story, once in Scotland, the Order continued with the ‘usages of Masonry…chosen to preserve the memory…’ and that ‘nobody was admitted a Scots Master, other than a child of the Order…’ The Rite in celebrating Scotland and its secret Templar heritage, seems to echo the chivalric ideas presented in the ‘Oration’ of Chevalier Ramsey, something that was also mirrored in the Rite’s suggestion of a mysterious Jacobite source.

Indeed, Baron von Hund’s undoing was the mysterious origins of the Rite, and being unable to present any tangible proof of his ‘unknown superiors’, a result of which his story became untenable and his reputation damaged. He died in 1776 in much reduced circumstances. At the convent of Wilhelmsbad in 1782, von Hund’s Rite quickly unravelled as a collection of delegates renounced the unproven Templar origins, they discarded the myth and a complete re-working of the ritual took place, ending the practice of von Hund’s Rite of Strict Observance. Some Masonic writers, such as Waite, have made reference of the supposed Jacobite origins of von Hund’s Rite; in Paris, von Hund believed he came into contact with a certain Knight of the Red Feather, whose identity was never revealed, but von Hund believed was none other than the Young Pretender Charles Edward Stuart. Waite was of the opinion that von Hund was mistaken or deceived, but either way, the Baron maintained his story until his death and the Rite of Strict Observance was, for a short while, one of the most progressive Rites in Europe during the eighteenth century. Despite the end of the practice of von Hund’s Rite of Strict Observance, its restructuring by Jean-Baptiste Willermoz led to the birth of the Rectified Scottish Rite, which will be discussed in more depth later. The Rite of Strict Observance also became an influence on the Rite of the Philalethes.

The Order of the Gold and Rosy Cross

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (also ascribed to Anton Graff), Portrait of Georg Forster (Member of the Gold and Rosy Cross), circa 1785

The Order of the Gold and Rosy Cross which was founded in Germany in the 1750s was perhaps one of the most mysterious esoteric Masonic Orders that came into being. The principle founder of the Order was the alchemist Hermann Fichtuld, and indeed, alchemy was a fundamental part of the teachings of the Order. Only Master Masons were considered to be members, and the Order attracted a number of influential German Freemasons such as Georg Forster. Forster was a leading intellectual figure of the Enlightenment; he had accompanied his father Johann Reinhold Forster on Captain Cook’s second voyage, whose duty was to record and write a scientific report on the voyage’s discoveries, which led to the publication of A Voyage Around the World on their return. Georg Forster went on to become a Fellow of the Royal Society and worked in a number of German Universities, later embracing the French Revolution and becoming a leading light in the formation of the Mainz Republic. He died in exile in Paris in 1794. King Frederick William II of Prussia was also involved in the Order of the Rosy Cross, the king being friends with the Freemason Voltaire and surrounding himself with artists, writers, musicians as well as supporting science. Frederick William was said to have been a ‘firm believer in the healing power of an elixir known to the Order’

Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Portrait of Giuseppe Balsamo (called Count Alessandro Cagliostro), circa 1786, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Of all the Masonic Rites that existed on the Continent during the eighteenth century, Count Alessandro Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite is perhaps one of the most intriguing and fascinating Rite. Cagliostro himself was a man of mystery, of ego and of creativity; the theatre of Freemasonry being the backdrop to portray the themes of alchemy and magic, something that appealed to many at the time. Cagliostro became the romantic subject of writers such Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Alexandre Dumas, and the romance surrounding his life seems to blur between fantasy and reality, creating an almost mythical Masonic character. For example, Cagliostro allegedly met illustrious eighteenth century personalities such as the Comte de Saint-Germain and Casanova, and Cagliostro’s past was as mysterious as these two figures, the magician being identified as Giuseppe Balsamo, an Italian forger and trickster. While in France in the 1780s, Cagliostro was implicated in the Affair of the Diamond necklace, which involved Marie Antoinette, and after spending time in the Bastille, he was released and left for England, later leaving for Rome, where he was arrested for being a Freemason in 1789. After trying to escape from the Castel Saint’Angelo, Cagliostro was moved to the Fortress of San Leo, where he died soon after.

Cagliostro became such an important figure in Freemasonry at the time that he was invited to the Convention of Paris in 1784 to explain his system, a Convention that the Rite of the Philalethes had been instrumental in organising. His claims included that he could renew youth, he could conjure the apparitions of the dead, he could bestow beauty on those who submitted to his system of Hermetic medicine, and that he could make gold. In short, his Rite would reveal the true hidden mysteries of nature and science, and as it became open to women, he began to attract a number of high-ranking ladies. Cagliostro’s particular form of Freemasonry has continued to attract speculation associated with the more libertine lifestyles of late eighteenth century France. Another more recent theory has put forward that a type of acacia was actually used in particular rituals to produce a psychedelic effect. Masonic researcher P.D. Newman has recently suggested that acacia was used in Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite for this purpose, and in a transcription of the ritual, acacia is identified as the ‘primal matter’ that was ‘created by God’, Newman suggesting it contained DMT. Indeed, the ritual conveys that this primal matter was known and ‘enjoyed’ by ‘Moses, Enoch, Elias, David, Solomon, the King of Tyre, and other great ones’, suggesting that acacia was an essential ritualistic ingredient. Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite allowed alchemy to be explored within the Masonic framework and the ritual certainly acted as a form of teaching for alchemy, the catechism explaining how to ‘bring about the marriage of the sun and the moon’ and that the rite allowed for the search for the ‘philosopher’s stone’ itself.

The Swedenborg Rite

Carl Frederik von Breda, Portrait of Emmanuel Swedenborg, before 1818, Glencairn Museum

Emanuel Swedenborg has never been proven to be a Freemason, he was however a mystic, theologian, philosopher, scientist and inventor, whose teachings and work inspired the Swedenborg Rite. Emanuel Swedenborg was born in Stockholm in 1688, his father being a Professor of theology at Uppsala University and later Bishop of Skara. Swedenborg was a learned man; inventing flying machines, researching anatomy and undertaking many different studies into various aspects of learning, being a propagator in the search for the hidden mysteries of nature and science. It was later in life that Swedenborg had a spiritual awakening of sorts which witnessed a transition from a man of science to a mystic; a man who could talk to angels, spirits and demons, and who discussed the second coming of Christ and the last judgment. Swedenborg died in London in 1772, and he went on to inspire eminent artists and writers such as William Blake and Thomas De Quincy, as well as fellow men of mysticism such as Louis Claude de Saint-Martin. It was after his death that the Swedenborg Rite was developed by a Polish Count and Swedenborg enthusiast called Thaddeus Leszczy Grabianka and Dom Antoine Joseph Pernety, fusing Swedenborg’s mystical teachings with certain Masonic ideas.

Dom Antoine Joseph Pernety had left the Benedictine Order and, after settling in Avignon, pursued his interests in alchemy. He then relocated to Berlin, becoming librarian to the Freemason Frederick the Great, and while there, he translated Swedenborg’s works into French. It was in Berlin that Pernety met the Polish Count Thaddeus Leszczy Grabianka, and after Pernety returned to Avignon, Grabianka joined him and they both founded the Société des Illuminés d’Avignon in 1786. This ‘Swedenborg’ Rite was relatively short lived, coming to an end in the wake of the chaos brought by the French Revolution. They did however attract two English Swedenborgians of note; William Bryan and John Wright, who in 1789 ‘were initiated into the mysteries of their order’ and were introduced to ‘the actual and personal presence of the Lord’, who was conveyed by a ‘majestic young man…in purple garments, seated on a throne’, situated in an inner chamber ‘decorated with heavenly emblems’. This hints that the Rite reflected the Millennialism philosophies of Swedenborg, but what the rest of the ritual was like, we can only speculate. Another Swedenborg Rite surfaced with the occult revival of the later nineteenth century, again containing elements of Swedenborg’s mystical Millennialism.

Rite de Elus Coens

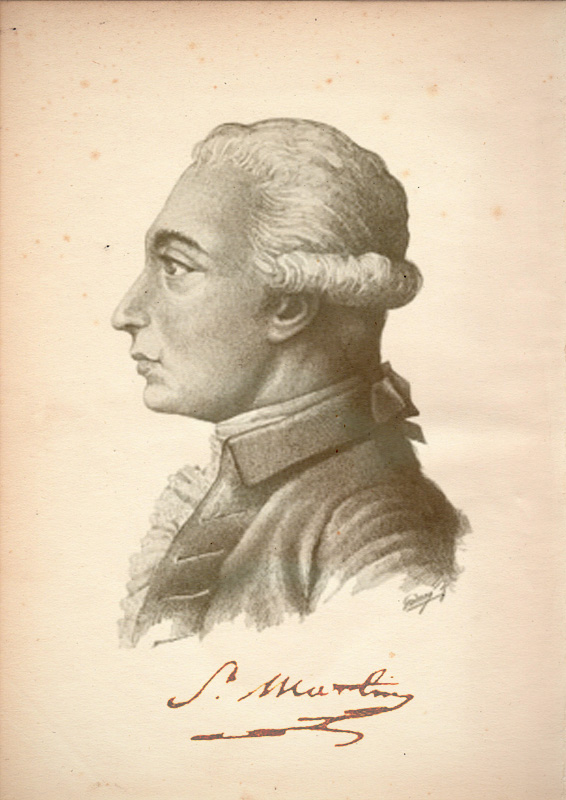

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin, unknown author, circa 1800

Martines de Pasqually established his Rite de Elus Coens (or the Rite of the Elect Priesthood) at Toulouse in 1760. The Rite had nine degrees divided into three divisions; these included the Porch, which were basically the three Craft degrees; the Temple, which were the chivalric degrees; and the Shrine, which more magical. Pasqually merged esoteric doctrines based on Gnosticism and the Cabbala, in short, his version of Freemasonry blending with magic to form a unique type of Rite. In this sense, the teachings of Rite de Elus Coens enabled its members to learn an aspect of magic that aimed to place the adept in communion with supernatural beings. Pasqually was particularly influential on Jean Baptist Willermoz and Louis Claude de Saint-Martin, both taking his teachings in different directions. When Pasqually died in 1774, elements of the Rite was absorbed into the restructured Rite of Strict Observance by Willermoz, creating the Rectified Scottish Rite, and his teachings went on to influence Martinism.

Dee and Kelley’s system of communicating with Angels was certainly similar to the work that was conducted almost two centuries later by certain members of Elus Coens, and was certainly reminiscent of Swedenborg’s mystical beliefs, the search for lost knowledge being a dominating theme of these Rites. Willermoz received training as a member of the Elus Coens by Pasqually himself, training that took place outside the lodge and was not part of any lodge room working, but was to be practiced alone and in private. Despite this, the training was an essential part of Pasqually’s teachings and Yarker in his Arcane Schools mentions that these teachings were part of the seventh Rose Croix degree.

Between 1768 and 1772, Willermoz received instruction from Pasqually ‘in occult or magical procedure’, these included not eating meat, conducting the ritual three days at the beginning of either equinox – the ritual to be performed at midnight, and to wear particular clothing while being divested of metals. A circle of retreat was to be drawn in the west side of the room with ‘the proper inscriptions at the proper points, with the symbols and wax tapers’, with a segment of a circle drawn on the east side of the room. After lighting all the tapers, the name of God was supplicated, and the names of the inscribed Angels were recited, being asked ‘to grant that which was desired…’ However, in spite of his dedication, Willermoz only reported seeing visions of colours, sparks and goose bumps, ultimately becoming dissatisfied with the results. His close friend and colleague Saint-Martin – the ‘Unknown Philosopher’ – believed that there could be a direct communion between man and God, and that ‘we are all Christs’.

Around 1770, Pasqually gave Willermoz further instructions, with the circle of retreat being located in the centre of the room, but by 1772, Pasqually left for St. Domingo, never to return. As Waite enigmatically puts forward ‘I do not doubt that Willermoz and his circle received psychic communications’, Willermoz and Saint-Martin’s explorations for the search for lost knowledge pushing the boundaries of this world…and that of the next. As Waite reminds us ‘the Ceremonial Magic of the Elect Priesthood is by no means fully available…’ and there were certain invocations and descriptions that were not written down, so the little we do know gives us but a glimpse of Pasqually’s occult workings. We do know however that part of their doctrine featured a belief system of the Fall of the Man and the restoration of man as a divine agent, being able to commune directly with God.

The lost Rites of the eighteenth century were a reaction to the fashion of Freemasonry that swept the Continent at that time; Rites created by charismatic gentlemen such as Count Cagliostro, Baron von Hund and Melissino, who constructed intricate rituals and for a time, attracted quite a dedicated following. The arcane nature of some of the lost Rites certainly reflects the way that the secret practice of Angelic and spiritual communication was an integral part of the teachings within the particular Rite. The teachings of Pasqually in the Rite de Elus Coens are perhaps the best example of this practice of spiritual communication, along with the Angelic communications that are discussed in Cagliostro’s ritual and the hints of spiritualism that may have taken place with members of the Order of the Rosy Cross. The search for the lost word of God that we still see today performed in the theatre of Craft Freemasonry and the Royal Arch, was boldly taken a step further in a number of these Rites, with Angelic communication being attempted in the search to gain hidden knowledge.

About the author

Dr. David Harrison is a UK based Masonic historian who has so far written nine books on the history of English Freemasonry and has contributed many papers and articles on the subject to various journals and magazines, such as the AQC, Philalethes Journal, the UK based Freemasonry Today, MQ Magazine, The Square, the US based Knight Templar Magazine and the Masonic Journal. Harrison has also appeared on TV and radio discussing his work. Having gained his PhD from the University of Liverpool in 2008, which focused on the development of English Freemasonry, the thesis was subsequently published in March 2009 entitled The Genesis of Freemasonry by Lewis Masonic. The work became a best seller and is now on its third edition. Harrison’s other works include The Transformation of Freemasonry published by Arima Publishing in 2010, the Liverpool Masonic Rebellion and the Wigan Grand Lodge also published by Arima in 2012, A Quick Guide to Freemasonry which was published by Lewis Masonic in 2013, an examination of the York Grand Lodge published in 2014, Freemasonry and Fraternal Societies published in 2015, The City of York: A Masonic Guide published in 2016, and a biography on 19th century Liverpool philanthropist Christopher Rawdon which was published in the same year.